The Politics of Hunger

- Gael MacLean

- Aug 10, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 10

When starvation becomes strategy

There is a peculiar quality to the language we use around famine, the way we reach for words like "tragedy" and "disaster," as if hunger descends like weather—random, natural, unavoidable. But spend any time examining the great famines of history, and you begin to see the architecture beneath the catastrophe. The blueprints. The signatures.

What emerges is this: famine is rarely about food. It is about power. About who matters and who doesn't. About which lives get counted and which disappear into statistics that will be disputed for decades. If you look closely at Gaza, at Sudan, at any place where hunger has become epidemic, you see not scarcity but strategy. Not shortage but systems.

The Mathematics of Deliberation

In Gaza, half a million people face starvation while someone, somewhere, maintains precise records of their dying—as if documentation were a form of action, as if knowing could substitute for preventing. The bureaucracy of death has its own vocabulary: IPC Phase 5, catastrophic food insecurity, famine thresholds. But beneath these clinical terms lies something more primal—organized groups ransacking homes for anything edible, from crops to personal food supplies to pets.

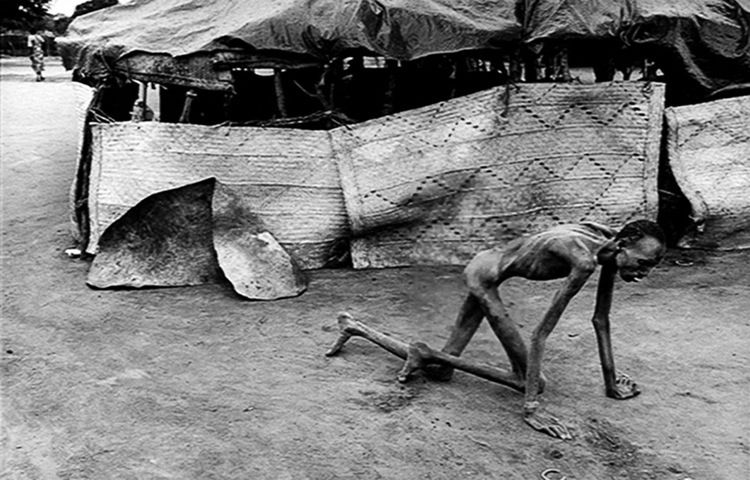

There is something peculiarly modern about being able to watch this unfold on our phones. We scroll past images of starving children between coffee orders and work emails. The compression of distance—technological, temporal, emotional—should mean something. Should change something. Instead, we've developed a new kind of looking that doesn't quite register as seeing. The children become content. The famine becomes a feed. The dying becomes data.

In Sudan, the dying comes with its own meticulous accounting. More than 24 million people face acute food insecurity—half the country's population reduced to a statistic. In North Darfur alone, 635,000 people are experiencing conditions worse than anywhere else on earth, eating hay and peanut shell animal feed while that too runs out. Yet somehow we also know that exactly 646 people starved to death in the Nuba Mountains by October 2024—not 645, not 650, but precisely 646. What does it mean that we can be so exact about individual deaths while 635,000 others face mass starvation? The precision itself becomes part of the horror—this careful cataloguing of preventable deaths, as if accuracy in counting could somehow matter to the dead or the dying.

These aren't natural disasters. Both the SAF (Sundanese Armed Forces) and RSF (Rapid Support Services) are using starvation as a weapon, and everyone knows it. The repetition itself becomes part of the machinery—the same places, the same methods, the same international response of documentation without prevention. We've created a world where you can watch people die of hunger on satellite feeds while humanitarian supplies sit just outside their reach, and call this normal.

The Colonial Laboratory

The Bengal Famine of 1943 offers a template for understanding how political calculation transforms into mass death. Three to four million Indians died not because food wasn't available, but because India was exporting more than 70,000 tons of rice even as the famine set in. Churchill's response to telegrams depicting the devastation was telling: "Then why hasn't Gandhi died yet?"

The vicious irony seemed lost on him—that Gandhi had repeatedly used voluntary hunger strikes as a weapon against the empire while Churchill was using involuntary starvation as a weapon to preserve it. The colonial apparatus had developed its own moral accounting, with British officials arguing that "the starvation of anyhow underfed Bengalis is less serious than sturdy Greeks." As if flesh could be weighed on scales of empire, as if some deaths mattered less by virtue of geography and skin color.

The Technology of Erasure

Stalin's Holodomor in Ukraine reveals how bureaucracy perfects brutality. Around 3.9 million Ukrainians died during 1932-1933—28,000 people every day at its peak, 1,168 people every hour, 20 people every minute. But these numbers miss the intimacy of the killing. Brigades used long wooden poles with metal points to probe dirt floors around peasants' homes, searching for hidden grain. They created "black boards" regimes—complete food blockades involving total seizure, bans on trade and travel, military encirclement.

The state provided some food to villages, but mainly as public catering and only to collective farmers who could still work. The rest were left to die. What strikes me is the calculation involved—the decision to feed some and starve others, the bureaucratic machinery that could make such distinctions. Someone had to write these policies. Someone had to enforce them. Someone had to sleep at night knowing exactly what they were doing.

Mao's Great Leap Forward perfected this bureaucracy of starvation. Between 1959 and 1961, somewhere between 15 and 55 million Chinese starved to death—the uncertainty itself a kind of violence, the dead reduced to a range estimate. The mechanism was elegant in its simplicity: local leaders inflated production figures, so the state seized crops based on phantom harvests. Meanwhile, 22 million tons of grain sat in public granaries while people ate bark and roots.

The Architecture of Denial

Every engineered famine shares certain structural features, like a blueprint passed down through centuries of systematic killing. First comes the blockade—physical, economic, or both. In Yemen, Saudi Arabia deliberately targets the means of food production by bombing farms, fishing boats, ports, food storage facilities. Almost a third of all coalition airstrikes have aimed at civilian targets.

I think about what it means to know this—that we can track airstrikes, categorize targets, calculate percentages in real-time. Somewhere, an analyst is updating these statistics. Somewhere else, a pilot is receiving coordinates for the next strike on a fishing boat. Both actions exist in the same moment, the same world, as if they have nothing to do with each other.

Then comes the denial of the crisis itself. During the Irish Potato Famine, up to 75 percent of Irish soil was devoted to wheat, oats, and barley grown for export and shipped abroad while people starved. British officials argued that "God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, and that calamity must not be too much mitigated."

Consider the strange comfort of invoking God here—how it transforms human decision into divine will, policy into providence. The ships loaded with grain sailing past the starving. The ledgers recording both the exports and the deaths. The bureaucrats who could sleep at night because they'd found a story that made their choices inevitable.

Finally comes the rewriting of history. China still refers to its famine as "Three Years of Natural Disasters." The Soviets denied the Holodomor entirely until 1987. These aren't mere propaganda efforts—they're attempts to erase the technology of famine from collective memory, to ensure it can be deployed again without the inconvenience of historical precedent.

The Contemporary Machinery

Gaza presents famine as real-time spectacle. More than 90 percent of the population faces crisis-level hunger while WHO medical supplies and food sit just outside Gaza's borders—ready for deployment, safeguards in place, bureaucracy complete. The actions needed to prevent famine are not mysterious. Everyone knows what would stop the dying. The dying continues anyway.

The sophistication lies not in hiding the strategy but in its bureaucratic legitimation. By the time a situation officially reaches IPC Phase 5—famine—the technical thresholds have been met, the proper classifications assigned, the paperwork filed. We've created a system where mass starvation can be processed through proper channels.

In Sudan, funding cuts have led to the closure of emergency food kitchens, while projections indicated correctly that five more areas would succumb to famine by May 2025. The war has become, as one report puts it, "using the threat of starvation as a bargaining tool." What's striking is how openly this is acknowledged now—starvation as strategy is no longer something to hide but something to factor into equations.

"I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. The events I have recorded should not be forgotten and must not be repeated." —James Nachtwey

The Moral Calculus

What distinguishes political famine from natural disaster isn't just intent—it's the calculation involved. Someone, somewhere, runs the numbers. How many can die before international pressure becomes unbearable? How many images of starving children can the global community absorb before intervention becomes inevitable? These aren't rhetorical questions—they're actuarial ones.

In Yemen, by the end of 2021, at least 377,000 Yemenis had died, with over 60% of deaths due to disruptions in access to food, water, and medicine. These aren't casualties of war in any traditional sense—they're the products of actuarial warfare, where survival becomes a matter of political math and human beings become acceptable losses in someone else's spreadsheet.

The Grammar of Justification

Every famine develops its own vocabulary of denial. Natural disaster. Market forces. Military necessity. Terrorist activity. These words do double work—they describe and they absolve. They transform political choices into atmospheric conditions, human decisions into inevitable forces.

Churchill had his theory about Bengal: the famine was the fault of Indians for "breeding like rabbits." Stalin blamed Ukrainian nationalism and kulak sabotage—'kulak' being his elastic term for any farmer who resisted collectivization. Mao pointed to floods and droughts. The Saudis cite security concerns and Iranian weapons shipments. The grammar changes but the structure remains: the starving are always somehow responsible for their starvation.

There's a peculiar intimacy to this blame—the killers always seem to know their victims well enough to explain why they deserve their fate. They've bred too much or too little, resisted too much or too little, believed the wrong things or believed them too fervently. The rhetoric reveals a relationship, however twisted. You don't need to justify killing those you don't see as human. The justification itself is an admission of recognition.

But I keep thinking about the people who create these justifications. The colonial official who writes "breeding like rabbits" in a report. The party apparatchik who types "kulak saboteur" on a death list. Do they pause, even for a moment? Or does the language itself become a kind of narcotic, numbing the nerve endings of conscience until mass murder feels like policy implementation?

The International Architecture

Modern famines operate within a complex international system that both enables and occasionally constrains them. The UN's Integrated Food Security Phase Classification system, with its five phases and technical thresholds, creates a scientific veneer that can paradoxically delay action. We've bureaucratized starvation so thoroughly that dying people must wait for proper classification before receiving help.

The international community's response follows predictable patterns. First, denial or minimization. Then, limited humanitarian aid that must navigate the very blockades and restrictions that created the crisis. Finally, after the dying has largely ended, come the investigations, the reports, the promises of "never again." But the architecture remains intact, ready for the next deployment.

The Persistence of Method

"There was no bread, no potatoes, nothing. A woman across the lane boiled her son. People whispered, but no one had the strength to be outraged. We were all shadows, and shadows feel nothing."

Testimony of Petro H. from the Soviet archives and survivor testimonies regarding cannibalism during the 1932–33 famine in Ukraine. (recorded by British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, 1933)

What's remarkable about famine as a political tool is how it transcends ideology. Capitalist empires, communist states, military dictatorships, theocratic movements—all have discovered the same basic truth: hunger is a uniquely effective weapon. It kills slowly enough to allow for plausible deniability, quickly enough to achieve political objectives.

The pattern repeats with mechanical precision: Bengal exports grain while millions starve. Ukraine ships wheat while peasants eat their children. China reports record harvests while 30 million die. Yemen's borders remain sealed while 377,000 perish. Gaza's aid sits at checkpoints while half a million face starvation. Sudan's food kitchens close while famine spreads.

These aren't failures of the international system—they're features of it. Each famine teaches the next generation of killers how to refine their methods, how to perfect their denials, how to maintain plausible deniability while engineering mass death.

The Question of Tomorrow

In her essay "On Keeping a Notebook," Joan Didion wrote about the necessity of remembering "what it was to be me." When we examine famine, we must remember what it is to be us—a species capable of engineering mass starvation while maintaining elaborate structures of denial.

The technology of famine has been refined but not fundamentally altered. The blockade, the extraction, the denial, the rewriting—these remain constant. What changes is our capacity to witness it in real-time, to see the architecture as it operates. Satellite images show us the graves being dug. Social media brings us the voices of the dying. The UN provides precise classifications and percentages.

Yet the dying continues, because knowing and preventing occupy different universes of action.

Perhaps the most disturbing revelation isn't that famine is political—it's that everyone knows famine is political. The reports are written, the mechanisms documented, the patterns established. We have centuries of evidence, meticulously archived. We know exactly how it works and why it works and who makes it work.

And still, somewhere right now, someone is running the numbers. Calculating how many can die before international pressure becomes unbearable. Preparing the rhetoric of denial. Building the architecture for the next deployment of hunger as strategy.

The question isn't whether it will happen again. The question is where, and when, and how many will disappear into the statistics that historians will dispute decades from now, parsing the difference between 15 million and 55 million deaths as if precision in counting could somehow retroactively matter to the dead.

What remains is the terrible clarity of it all—the knowledge that behind every famine stands not nature but choice, not scarcity but system, not tragedy but technique. In the end, that may be the most unbearable fact: that we know exactly what we're doing, and we do it anyway.

The politics of hunger, it turns out, isn't really about hunger at all. It's about who gets to decide who lives and who dies, and how we've constructed a world where that remains—despite everything we know, despite everything we've seen—a legitimate political question.

And perhaps that's the most damning indictment: not that we use starvation as a weapon, but that we've built a world where it works so efficiently, so repeatedly, so openly that we barely pretend to be shocked anymore when it happens again.

"Starvation is nothing but death. If we have to lose a few million, so be it." —Mao Zedong, (1959)

Header Image ©2025 Gael MacLean