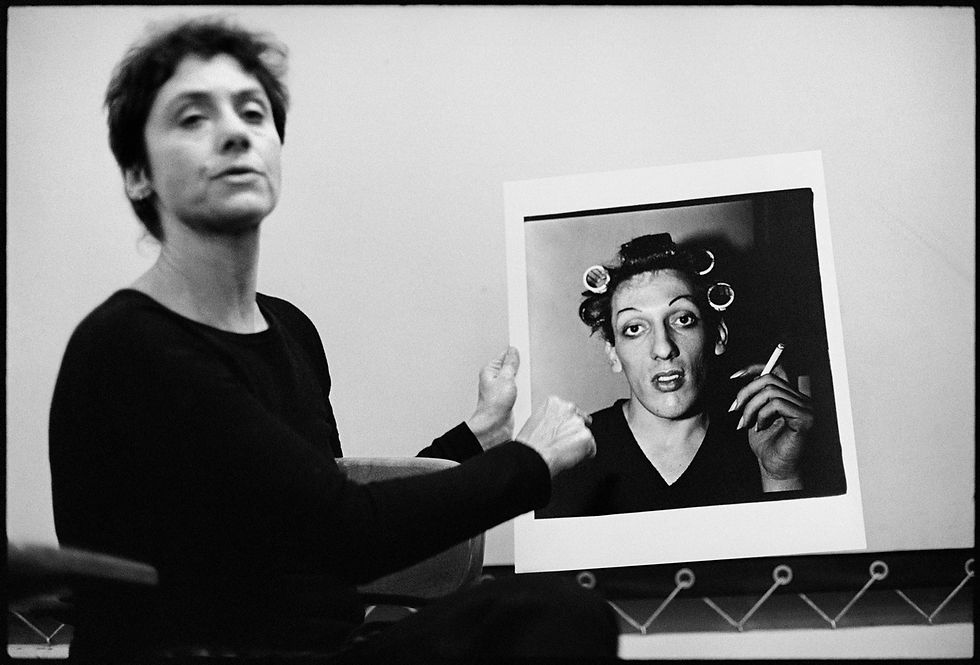

A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street

- Gael MacLean

- Sep 22, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 10

Diane Arbus and the pursuit of authentic humanity

A hot New York summer. 1966. Her Rolleiflex hanging from her neck, Diane Arbus found herself on West 20th Street. The air was thick with possibility. The faint scent of developing fluid followed her everywhere. She was hunting for evil. Or so she said. But what did evil look like in the sweltering streets of Chelsea?

Evil was not what she found when she knocked on the door of a nondescript brownstone. Instead, she encountered a young man named Marcus. His head adorned with plastic curlers, a cigarette dangling from his lip. In that moment, Arbus saw not evil, but a raw, unvarnished truth. The kind that makes most people look away. But drew Arbus in like a moth to flame.

Marcus invited her in. Not because he knew her work or her growing reputation, but because in her intense gaze he recognized a kindred spirit. Someone else who lived on the fringes. Who understood the power of masks and the pain of removing them.

The apartment was a cluttered shrine to a life in transition. Wigs of various colors were perched on styrofoam heads. Mascara wands and lipstick tubes littered every surface. The air was heavy with the scent of hairspray and stale smoke. It was a cocoon, Arbus thought, where metamorphosis was a daily ritual.

As she set up her camera, Marcus spoke of his life. Of growing up in a small town in Ohio where he never quite fit. Of coming to New York with dreams of Broadway lights and finding instead the flickering neons of dive bars and drag shows. He spoke of the first time he put on a dress. How it felt like coming home to a place he’d never been.

Her finger hovering over the shutter release, Arbus listened. She was not photographing evil. She was documenting resilience. The fierce determination to exist authentically in a world that demanded conformity.

“People like to believe they know who they are,” Arbus would later write in her journal. “They cling to it. But the truth is, we are all actors, all the time. Marcus just has the courage to admit it.” — Diane Arbus Documents

The photograph she took that day — Marcus looking directly into the camera, curlers in his hair, cigarette in hand — would become one of her most iconic images. It was not a portrait of evil. But a challenge to a society that was all too eager to label and dismiss what it didn’t understand.

In the years that followed, Arbus would return to West 20th Street many times. She watched as Marcus’s transformation continued. As he found his place in the burgeoning world of underground theater and the nascent gay rights movement. She documented his triumphs and his struggles. The nights of glitter and glamour and the mornings after, when the makeup was smeared and the illusions fell away.

Their relationship was complex. A dance of subject and artist. Of confessor and penitent. Marcus would later say that Arbus saw him more clearly than anyone ever had. Her lens stripped away the layers of performance until only the essential remained.

But what was that essential truth? Was it the young man in curlers, vulnerable and defiant? Or was it the drag queen who commanded stages with a presence that made audiences forget to breathe? Or was it something in between? Something that defied easy categorization?

Arbus’s quest to capture what she called “evil” was perhaps misunderstood by many. Even by herself at times. What she was seeking was the unvarnished reality of human existence. The moments when the masks slip and we are forced to confront the complexity of identity. And the fluid nature of self.

In Marcus, she found a willing collaborator in this exploration. He understood, instinctively, that to be seen — truly seen — was both terrifying and liberating. Each click of Arbus’s camera was an act of revelation. Peeling back layers to expose the raw nerves beneath.

Marcus would later say that Arbus saw him more clearly than anyone ever had. Her lens stripped away the layers of performance until only the essential remained.

As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, the world around them changed. The Stonewall riots erupted just blocks from Marcus’s apartment. And suddenly the private acts of defiance that Arbus had been documenting for years spilled out onto the streets.

Marcus was there, in the thick of it, no longer hiding behind closed doors but marching proudly. His face painted and his voice raised in protest. Arbus photographed him then too. Her images capturing the euphoria and the fear. The sense that something monumental was shifting.

But even as the world began to change, Arbus found herself increasingly drawn to the quiet moments. The in-between spaces where identity was fluid and uncertain. She returned again and again to that first image of Marcus. The young man in curlers, caught in the act of becoming.

In her later years, when asked about her work and her subjects, Arbus would often deflect. Saying simply, “I never wanted to prove anything. I wanted to show everything.” And in Marcus, she found everything — beauty and pain, strength and vulnerability, the mundane and the extraordinary existing side by side.

The last time Arbus visited West 20th Street was in the spring of 1971. Just months before her death. Marcus greeted her as he always had, with a cigarette and a wry smile. They didn’t take any photographs that day. Instead, they sat by the window, watching the city below. Two outsiders who had found in each other a kind of understanding that transcended words.

Years later, when the photograph of Marcus in curlers hung in galleries and museums around the world, viewers would stand before it. Searching for the evil that Arbus had claimed to seek. But those who looked closely saw something else entirely. A portrait not of deviance or otherness. But of humanity in all its complex, contradictory glory.

In the end, perhaps that was Arbus’s greatest gift. The ability to show us not the evil in the world, but the beauty in what society too often cast aside. Through her lens, Marcus became not a curiosity or a freak, but a testament to the indomitable human spirit. To the courage it takes to become oneself in a world that so often demands conformity.

And in that, there was nothing evil at all. There was only truth, raw and uncompromising. Captured forever in black and white.

Diane Arbus was an American photographer known for her striking black-and-white portraits of people on the fringes of society. Born in 1923 in New York City, she began her career in fashion photography with her husband Allan Arbus. In the 1950s, she struck out on her own, developing a unique style that focused on subjects like circus performers, transgender individuals, and people with disabilities.

Arbus had a knack for capturing the unusual and often unsettling aspects of her subjects, earning both praise and controversy. Her work gained significant recognition in the 1960s and beyond. Arbus died by suicide in 1971 at the age of 48. She had struggled with depression throughout her life.

Arbus left a lasting impact on photography and is now considered one of the most influential American photographers of the 20th century.